Several weeks ago, for Corpus Christi, we heard John 6, the “Bread of Life” Discourse, read in Mass. This is a pivotal text for Catholics’ understanding of the Real Presence in the Eucharist. Just as Christ’s teaching divided His followers 2,000 years ago, the doctrine today is still a source of disunity among Christians. What are some interpretative tools that Catholics use when reading the “Bread of Life” Discourse to support the dogma of the Real Presence in the Eucharist? Here are 6 keys to interpret John 6:

- The immediate context. The immediate context of Jesus’ words that His flesh is real food and blood real drink was literal. Jews took Jesus to be speaking literally. When followers balk at the teaching, Christ doesn’t correct their literal understanding. He loses followers for the teaching. He does, however, correct followers’ misinterpretations of other teachings, such as recorded in Matthew 16:5-12. Therefore, we know He corrects misunderstandings when necessary. The case is that these followers, taking Jesus literally, were not misunderstanding Jesus here. We must consider how the people who were hearing Jesus at that time interpreted what He said as recorded in John 6. Many of Christ’s followers were so scandalized by the concept of eating his flesh and drinking his blood that they left him. They would be unlikely to have had such a harsh reaction if they believed He was speaking figuratively.

- The cultural significance. The language that was spoken at the time, and the phrases and modes of speaking in use at the time, are important to interpret Jesus’s words and intentions accurately. It is important to note there was already a figurative meaning to “eating flesh.” “Eating flesh” taken figuratively in First Century Judaism meant to conquer through hostile action, obliterate, or annihilate (see same usage in Ps 27:2, Zec 11:9). The passage in John 6 makes no sense reading on a symbolic level if you consider the original language in which the teaching was given. “Whoever “annihilates” me has eternal life” is nonsense. Further, the drinking of blood in Judaism was looked upon as a horrendous thing forbidden by God’s Law (Gen 9:4, Lev 3:17, Dt 12:23, and Acts 15:20). Outside of Temple rituals, the symbolic meaning of ‘drinking blood’ was that of brutal slaughter (Jer 45:10). The life was in the blood, and God forbade His people from drinking animal blood. Why? He wanted them to have divine life through the blood of Christ, not animal life through the blood of animal sacrifice.

- The relationship between flesh and blood to the word ‘spirit’ in Sacred Scripture. The reader must distinguish the difference between “my flesh” and “the flesh” as Jesus spoke about them, in relation to how these phrases are used in other areas of Scripture. Jesus ends the discourse with the flesh is of no avail. He doesn’t say My flesh is no avail. The flesh has a special meaning. See I Cor 2:14. The flesh refers to someone who is living without the Holy Spirit. What Jesus is saying in John 6 is that His followers can’t understand this teaching of the Real Presence in the Eucharist with mere human reason alone. They need the Holy Spirit to comprehend and accept it- that’s what Jesus is saying when He says, “the flesh is of no avail.”

- The analogy of faith. The coherence of the truths of faith among themselves and within the whole plan of revelation need to be understood in light of all other truths. I Cor 11:24 tells us what Jesus told Paul about the Eucharist. Then Paul goes on to describe people profaning the body of the Lord by eating unworthily. If it’s just a symbol, how is it profaning?

- The Greek terms that John uses to convey Christ’s words. The Greek word trogein means to gnaw or chew on and Christ uses this, doubling down on His teaching after followers murmur. It is doubtful that Christ would use that word if He was speaking figuratively, yet He does use this emphatic word when the followers question the eating.

- How the Early Church wrote about the Eucharist. There are many writings from the Early Church Fathers that leave little room for misinterpretation about their belief in the True Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The Didache, written in approximately 90 AD, St. Ignatius of Antioch’s letters from around 110 AD, and Justin Martyr’s apologies from 150 AD, are some of the earliest mentions of what the Church has always taught about the Eucharist. See excepts below from each.

And let the bishop give the oblation, saying, The body of Christ; and let him that receiveth say, Amen. And let the deacon take the cup; and when he gives it, say, The blood of Christ, the cup of life; and let him that drinketh say, Amen (Didache) [1]

Be careful therefore to use one Eucharist (for there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup for union with his blood, one altar, as there is one bishop with the presbytery and the deacons my fellow servants), in order that whatever you do you may do it according unto God. (Epistles of Ignatius, “To the Philadelphians.”)[2]

They abstain from Eucharist and prayer, because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ who suffered for our sins, which the Father raised up by his goodness (Epistles of Ignatius, “To the Smyrnaeans”). [3]

And this food is called among us Εὐχαριστία [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.6 For the apostles, in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them; that Jesus took bread, and when He had given thanks, said, “This do ye in remembrance of Me, this is My body;” and that, after the same manner, having taken the cup and given thanks, He said, “This is My blood;” (First Apology of Justin Martyr) [4]

As recent studies suggest, Catholics, for various reasons, have fallen away from belief in the Real Presence. Yet our hope is in our Eucharistic Lord. May we, as our first pope exhorts, “always be prepared to make a defense to anyone who calls [us] to account for the hope that is in [us] (I Pet 3:15, RSVCE).

[1] Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, eds., “Constitutions of the Holy Apostles,” in Fathers of the Third and Fourth Centuries: Lactantius, Venantius, Asterius, Victorinus, Dionysius, Apostolic Teaching and Constitutions, Homily, and Liturgies, trans. James Donaldson, vol. 7, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1886), 490–491.

[2] Pope Clement I et al., The Apostolic Fathers, ed. Kirsopp Lake, vol. 1, The Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge MA; London: Harvard University Press, 1912–1913), 243.

[3] Pope Clement I et al., The Apostolic Fathers, ed. Kirsopp Lake, vol. 1, The Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge MA; London: Harvard University Press, 1912–1913), 259.

[4] Justin Martyr, “The First Apology of Justin,” in The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 185.

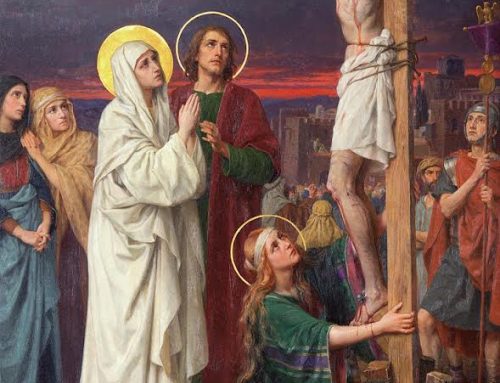

Supper at Emmaus, Caravaggio, 1601.

Leave A Comment